Dramatic Exchanges is Dan Rosenthal’s follow up to his 2013 The National Theatre Story, which traced the history of the National Theatre (NT) from its protracted, painful inception, through the era of each artistic director to the present day. Whereas The National Theatre Story provided a comprehensive and excellently researched history, Dramatic Exchanges provides the life, anger, drama and character that went alongside it.

Rosenthal’s research has uncovered a staggering range of letters, telegrams and emails and it makes one thankful for the archiving of correspondence that kept each letter for posterity. Will a book like this be possible in the future? How often are the contents of our often-rushed emails and whatsapp messages carefully thought over heartfelt glimpses into our feelings? Rosenthal whittled down over 12,000 letters to 800. Maybe there is something about the theatre that encourages letter writing. For actors, so used to speaking others’ words, does it give them the chance to put in place their own thoughts and ideas?

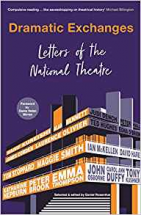

The first thing to say about this book is how attractive it is. Peppered with behind the scenes photos and telegrams it is a book to be cared for like the letters inside obviously have been. The prologue and first chapter give a glimpse into the pain and difficulty of the years dedicated to trying to establish a national theatre. Although championed by the literary greats setting up a theatre proved to be a very difficult task. George Bernard Shaw angrily compared the Irish and British attitudes to theatre and came away confused as to why “the English nation … has just enthusiastically given a huge sum of money to buy the Crystal Palace for the sake of the cup finals, but absolutely refuses to endow a national theatre”. It is quite funny to be reading a letter and then to check the names and realise it was written by Hardy, Yeats, Shaw and so on. It is an early indication that Dramatic Exchanges will be packed full of famous names and previously untold stories.

Laurence Olivier was the first artistic director of the NT, a role that he took on with mixed feelings. “At the moment it looks like the most tiresome, awkward, embarrassing, forever-compromise, never-right, thankless fucking post that anyone could possibly be fool enough to take on the idea and it fills me with dread.” Olivier was a prolific letter writer and used a wonderful mix of high and low language peppered with the very explicit. There is a particular pleasure in revelling in turns of phrase that are hardly ever heard any more.

The book is divided in ‘acts’ and after the early years the book is divided by artistic director – the Olivier years, the Hytner years and so on. If you want to skip ahead to find out about your favourite plays, actors and scandals this makes it easier to do. A very comprehensive index also helps. If choosing to read chronologically Rosenthal’s selections take you on a tumultuous journey through the years to the present day.

Letters give the reader an insight into the real thoughts and feelings of the letter writer at that time. They were not written for public consumption and as such are full of emotion. The arguing between different directors in particular can be vicious at times as each one tries to defend and enhance their own theatre space. Actors write to say how disappointed they are in not getting parts they were promised, bad press is ripped apart and blame apportioned. Here we see the private side to public battles. It is striking how often actors simply present themselves to the theatre asking for work or suggesting they play a certain role (even Sean Connery fresh from his success as James Bond) and how often they write asking for a second audition or another chance (even the now greats like Eileen Atkins). This is something that is enjoyable and fascinating for anyone with an interest in theatre history.

There are also some bright and pleasant exchanges too. For example, there was a lovely series of exchanges between Peter Hall and Sheila Hancock in 1985 as she became the first woman to direct at the NT, with her production of Sheridan’s The Critic. “Dear Peter, At one point in our recent meeting, you asked: “What would you like to do?”. I answered, as I always do when asked that, with a weak shrug. My new year’s resolution is no more weak shrugs, so here it goes…”. And soon – Arts Council and GLC permitting – she is working in the National as director and actor.

This is a beautiful collection to sit on any bookshelf and the theatre lover will find much to delight in. I’m probably not the only one drawn to the Olivier years. To go back to the birth of the NT with one of the nation’s greatest ever actors. And of course, before the advent of social media there are so many stories that have been buried in the archives for decades and are only now seeing the light of day. The general reader may want to start by finding their favourite actors or plays and reading up on those before approaching the book as a whole. Although this is an exceptional record of theatre correspondence it is debateable how much it will appeal to the general or casual reader.

For anyone with an interest in celebrity, the arts and theatre, Dramatic Exchanges is a brilliant addition to the bookshelf and after reading one is filled with considerable gratitude for Rosenthal and the archivists who made this book possible.